Ginseng adds a layer of possibilities for forestry

Understory intercropping has the potential to change how forests are planted in the future.

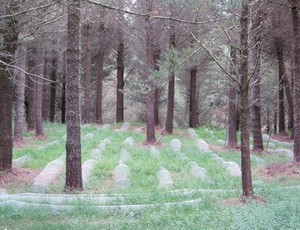

Neat rows of netting cloches lined up beneath well pruned radiata pine trees are in sharp contrast to the usual vision of a commercial planted forest block.

The small, unassuming ginseng plants beneath the cloches belie their potential to be a game changer in the profitability of forestry in New Zealand’s central North Island, and possibly other temperate zones across the country.

Research conducted recently by Scion for Māori forestry organisation Maraeroa C Incorporation, into where ginseng could grow within the central North Island and the additional value gained from growing it as an understory intercrop, shows promising results.

“We have appreciated the opportunity to work on this project with Maraeroa C and their motivated ginseng team, and we are all very excited about the results,” says Loretta Garrett, Project Leader and Soil Scientist at Scion. “Growing ginseng commercially as an understory intercrop could potentially double the profitability from the land compared to forestry alone over one rotation, which means huge benefits for the community and the economy.”

Ginseng has been used as a Chinese medicinal herb for centuries. The Chinese are the biggest users of ginseng and grow 90 per cent of the global crop. They also import large quantities from Korea and North America to supplement their own supply.

Several attempts have been made to grow the two better known Asian and American species here in New Zealand but until now, little research has been done into the critical environmental requirements for ginseng in this country or its value.

Maraeroa C has been trialling ginseng at its King Country estate since 2006 with the first crop due to be harvested in March next year. Along with particular soil, land slope and climate requirements, ginseng requires a high level of shade making planted forests an ideal environment in which to grow the herb.

Chief Executive of Maraeroa C, Glen Katu, approached Scion to help determine what the optimal conditions for growing ginseng were and other areas in the central North Island with similar conditions, as well as its economic value as an export.

“There are nearly 450,000 hectares of pine forests in central North Island, with Māori some of the biggest owners of forestry land in the area,” says Glen. “We wanted to scope the potential for them to grow ginseng as an understory intercrop, and the social impacts it may provide for these areas, the viability of overseas markets and what contribution ginseng may make to the country’s economy as a whole.

“Understory intercropping has the potential to change how forests are planted in the future to allow optimal spacing and a good environment for growing crops like ginseng.”

Ginseng is a slow growing perennial herb, taking 14 years to reach maturity in China but only seven years to reach maturity in New Zealand due to having twice the growing window than the snowy climates of North China and Korea. Naturally grown wild ginseng is considered the most valuable product, but years of severe over-harvesting means it now accounts for less than one per cent of the global production.

The majority of ginseng is cultivated - planted underneath artificial canopies or trees at high densities and subject to intensive chemical and mechanical treatment. The application of fertilisers means a shortened rotation and results in well fattened roots which are predominantly used in tonics or capsules or used as additives to soaps, shampoos, lozenges and such.  However, it’s the ‘wild simulated’ ginseng - planted in an environment close to its natural range, grown organically and harvested by hand - that commands prices second to those received for wild grown. This is the method that Glen and his team have been trialling, specifically targeting the largest and most demanding of markets.

However, it’s the ‘wild simulated’ ginseng - planted in an environment close to its natural range, grown organically and harvested by hand - that commands prices second to those received for wild grown. This is the method that Glen and his team have been trialling, specifically targeting the largest and most demanding of markets.

As Glen explains, the American species of ginseng promotes yin energy and is therefore cooling. This is often used by younger people or those in warmer climes. The Asian species is the yang energy, warming the body and being much favoured by older Chinese users – the largest segment of ginseng users worldwide.

“We saw a gap in the Chinese market for wild simulated ginseng – grown naturally with no fertilisers or pesticides used. Aesthetic attributes are just as important. It takes longer to grow and the roots are much smaller but are more highly valued. They are kept whole to be given as gifts, or sold to Chinese pharmacies for use in traditional medicines.”

In New Zealand, there is a growing window of about 15 years for ginseng as an understory intercrop to radiata pine; planted after final thinning from about 12 years when the canopy provides sufficient shade. Results of Scion’s research indicate its success as an understory intercrop will depend on specific soil, light level and climate, with a degree of winter chilling and positioned on gentle to undulating slopes for good air and water drainage, and site access.

Once the land is cleared, prepared and fenced to protect against grazing pests, ginseng seed is planted and then covered in netting to protect against birds. Seven or so years later, the roots can be harvested – in this instance, manually which Glen expects will take two or three minutes per root. Premium prices are achieved only if the root is undamaged and the myriad filaments and hairs attached to the root remain fully intact.

After drying, roots are packaged so their beauty and shape can be clearly seen. Any damage received to the root during harvesting relegates the product to second grade and is priced accordingly.

Although the risks are high, wild simulated ginseng may have a huge bearing on the profitability of forestry, providing earlier returns and considerable long term employment opportunities. Conservative estimates indicate ginseng could potentially double profitability compared to forestry alone, returning an additional 154 - 188 per cent value per hectare of planted forest. With an expected fresh yield of 675 kilos per hectare (225 kg dried) returning $2,000 per kilo for dried ginseng, the economics are clear.

Results of our research also indicate over half of the 450,000 hectares of planted forests in the central North Island has suitable environmental and geophysical conditions to grow wild simulated ginseng. The benefit for New Zealand’s economy could be huge.

Maraeroa C assisted six Māori forestry trusts install ginseng field trials on their estates last year. But as Glen says, they are assessing how it fares and no doubt, how Maraeroa C’s first harvest is received in the Chinese market.

The scoping ginseng research project was supported with funding from the Ministry of Primary Industries.

Contact

Loretta Garrett at: Show email

Glen Katu at: Show email

About ginseng

Two of the 11 species of ginseng are grown commercially. The Asian species (Panex ginseng) is thought to promote yang – hot, positive, male energy which warms the body, favouring people living in cold places. American ginseng (Panex quinquefolius) promotes yin, or cold, negative, female energy which cools and calms the body, making it more suitable for warmer months.

Ginseng is used as an all-round tonic to restore and enhance normal well-being. It is thought to boost energy, lower blood sugar and cholesterol, reduce stress, promote relaxation and treat diabetes. Ginseng’s main constituent, ginsenoside, is also believed to have anti-inflammatory properties.

Understory crops add flavour to forestry

Kawakawa is an indigenous species that is used for culinary, medicinal and cosmetic purposes.

Understory cropping may extend further than ginseng. Scion is working with Tarawera Land Company to improve the economic sustainability of their forested lands. The project centres on 21,000 hectares of radiata pine in the Kawerau region and is also exploring concepts for secondary crops within the wider Bay of Plenty.

“At present, most plantation forests in New Zealand are under-utilised,” says Project Leader Marie Heaphy. “We are looking at plant species that have the potential to grow as understory crops in radiata pine plantations, and provide earlier financial returns and diversified yields as well as employment opportunities for the region.”

Marie and Resource Economist Dr Richard Yao have analysed crops for site suitability, potential market and economic return. Of those found suitable for the Tarawera area, three were analysed in more depth – goldenseal and two native species, kawakawa and patē, all of which show promise.

Kawakawa is an indigenous species that is used for culinary, medicinal and cosmetic purposes. The market for kawakawa products is growing locally and overseas, and international demand for quality goldenseal root, used for herbal preparations, continues to exceed supply.

Contact Marie Heaphy: Show email