We need forests, but what type?

Our strategy “Right tree, right place, right purpose” is all about making sound decisions. One person’s right tree in the right place for the right purpose is not necessarily everyone’s so we must consider society’s different perceptions when working out where best to plant trees and change a land use. Our rural landscapes are familiar scenes, and fears about these landscapes changing from pasture to plantation forestry are understandable.

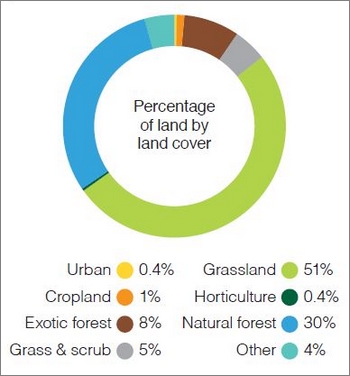

Yet land use facts should help allay those concerns. Planted forestry’s share is small – only 8 per cent – compared with land used for pasture, crops and horticulture¹.

“… it is hard to see what all the fuss is about when land use is already so heavily skewed to pastoral farming,” said Pattrick Smellie in the NZ Herald recently. I agree.

However, there is more to New Zealand forests than simply seeing exotic plantations for timber and fibre production versus indigenous forests managed for conservation values. There was an excellent reason for this dichotomy - exotic forests were planted to take pressure off our rapidly shrinking natural forests. It’s time we moved from this blanket view.

All our forests are affected by human activity. Increased atmospheric CO2 levels and expected increasing storm impacts will not spare any of our forests, and we must think more broadly in the conversation about the future of our forests.

Forests are a highly multi-functional land use fulfilling a primary purpose while giving many secondary benefits. They provide many products, like timber, fibre, energy, chemicals, food, medicines plus services such as carbon storage, erosion control, clean water, recreation, human wellbeing, biodiversity conservation, climate regulation and aesthetics.

A key challenge confronting us now is climate change. New Zealand committed to Paris Climate Agreement targets to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. Planting forests to store carbon from the atmosphere is part of the solution. The One Billion Trees Programme will contribute to this target over the next decade and is being promoted strongly, with payments to landowners to encourage planting.

The question is what type of forest? From a purely carbon perspective, fast growing exotic plantations are often the best and most effective approach. However, other perspectives and concerns, and other benefits sought from trees, must be considered when deciding on the ‘right tree’.

If we want to increase the carbon stored in trees there are many ways to do this across various forest types from untouched primary natural forest to trees outside forests.

For instance, if primary forests are affected by animal browsing, pest control could enhance tree growth and hence the amount of stored carbon; recovering natural forests could be fertilised to accelerate growth rates; and agricultural lands offer many options. A recent study² on sheep and beef farms has identified large areas of natural forests that could be actively managed to enhance carbon stocks.

If we look at new planting on agricultural land there are options that may not have too much effect on farm production. For example, we calculated the carbon stocks for running a 20 metre strip of radiata pine trees up both sides of all waterways in all farmland and came up with ~100,000 hectares and 100 million cubic metres of new forest at age 30, which equates to ~50 million tonnes of carbon sequestered, while only decreasing agricultural land area by ~1.0 to 1.3 per cent. New shelterbelts, spaced trees planted on less intensively farmed pockets are all additional places where carbon may be captured without too much impact on farm production.

Recent work³ has shown that existing plantation forests are not growing as fast as they could, so another approach to increasing carbon stocks is to intensify management across the existing 1.8 million hectares of planted forests. Current thinking is that it may be possible to double productivity, and hence carbon stored, through a combination of high performing genotypes, and tree crop and soil management.

These are just a handful of options but can help to expand our thinking. Discussion and communication of perceptions and understanding what we want from our forests and trees is important to good decision making by landowners, supported by a sound and commonly used scientific evidence base.

We need to plant new right trees in the right place for the right purpose, but we also need to make the most of the opportunities presented by our existing forests to integrate all forests into our national thinking and create new integrated landscapes for future generations to enjoy and use.

I welcome your thoughts on this topic and any other matters raised in this issue of Scion Connections.

Dr Julian Elder

Chief Executive

For further information contact

Dr Julian Elder

1 https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/23056-analysis-of-drivers-and-barriers-to-land-use-change2 https://beeflambnz.com/sites/default/files/FINAL%20Norton%20Vegetation%20occurence%20sheep%20beef%20farms.pdf

3 Moore and Clinton 2015. Enhancing the productivity of radiata pine forestry within environmental limits, NZJF. 60:3 pp35-41