Indigenous forestry renewed

New Zealand’s early forest industry was based on our indigenous forests. Over time, many of those forests disappeared, new sources of wood were sought and interest in indigenous trees languished. Indigenous trees were believed to be unsuited to planted forestry, being too slow growing and no match for the impressive growth that can be achieved with radiata pine. However, that’s not necessarily the case. Scion’s Greg Steward has spent more than four decades researching New Zealand’s indigenous trees for production forestry, and what he has learned may surprise you.

Beginnings

Planting of indigenous species began from as early as the mid 1800s. A 1919 review of kauri forestry revealed results that Greg has also observed: in managed plantations, kauri had significantly better growth than many exotic alternatives.

Despite these results, a pessimistic view of planted indigenous forestry had become embedded, based on early measurements and observations of growth rates in indigenous species that were contradictory and bleak. The prevailing assumption was that planted indigenous trees would have to resemble old growth forests to maximise clean timber and heartwood, and indigenous species would need hundreds of years to achieve this size.

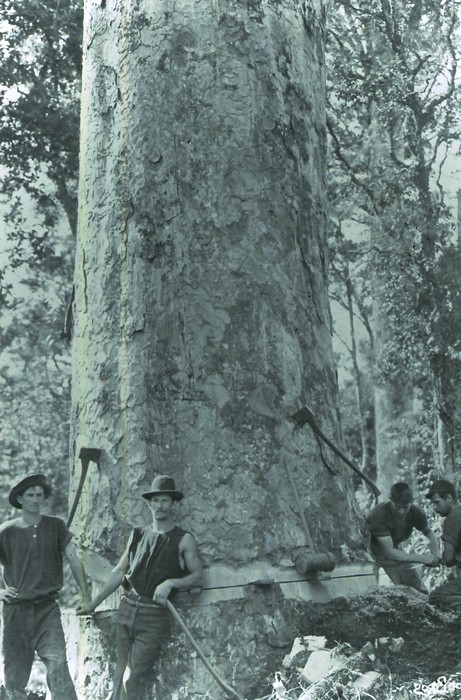

Indigenous forestry researcher Greg Steward visits one of the planted kauri stands he is studying.

Surprising results

Greg’s research into indigenous forestry dispels many of the old assumptions. He says, “indigenous forestry has been plagued by anecdotal conservatism”.

Weaving numerous sets of kauri growth data together, a pattern began to emerge of faster growth than was previously considered possible on sites within and outside the species’ natural range. Greg used this data to develop robust models of growth in planted stands. These models have shown that planted kauri stands aged 20 to 60 years were 20 times more productive than natural stands. His work has blown the estimated kauri crop rotations of hundreds of years out of the water.

Greg also found that if kauri is grown quickly, the wood quality does not diminish, unlike some exotic species. Reiterating the good news, Greg goes on, “we’re getting these great results before we’ve had an opportunity to apply selective breeding, which would improve performance again. There is so much opportunity here”.

Tōtara too has way surpassed initial expectations for crop rotations. Following research exploring growth, density and wood quality, estimations have been updated to a 60 to 80-year rotation, which is where Douglas-fir started in New Zealand and could be further reduced with research into breeding and management.

These findings give Greg hope for the future of indigenous forestry. “We need to unlock the economic opportunity in indigenous forestry, which will give people the confidence to invest while also helping to protect the future of our indigenous trees.”

Current research

Support has been provided from the One Billion Trees programme to remeasure progress on the old establishment trials. “We are looking at lessons we can learn from these trials, both good and bad.”

Research is also taking place in Northland with tōtara on private land. The most recent results (2019) are very promising, showing that self-seeded trees on farms growing without management or selective breeding still produce a high volume of good quality recoverable timber. However, Greg acknowledges there are still big gaps in our knowledge. “We desperately need species specific models on growth and productivity,” he says.

The three ages of forestry

In Greg’s opinion, there have been three ages of forestry in New Zealand. Forestry began with early land clearance, the second stage could be called the age of radiata pine, and the third age is what we are transitioning to now. Greg’s vision of the future includes a diverse forestry estate, with many different species that are planted for a variety of reasons.

Now approaching the last years of his career, Greg says he’s excited to see what Te Uru Rākau will achieve. And when asked what he’s most proud of in his 44 years of resolute and determined belief in indigenous forestry, he says, “maintaining the beating heart of where forestry started”.