The disappearance of kāuta

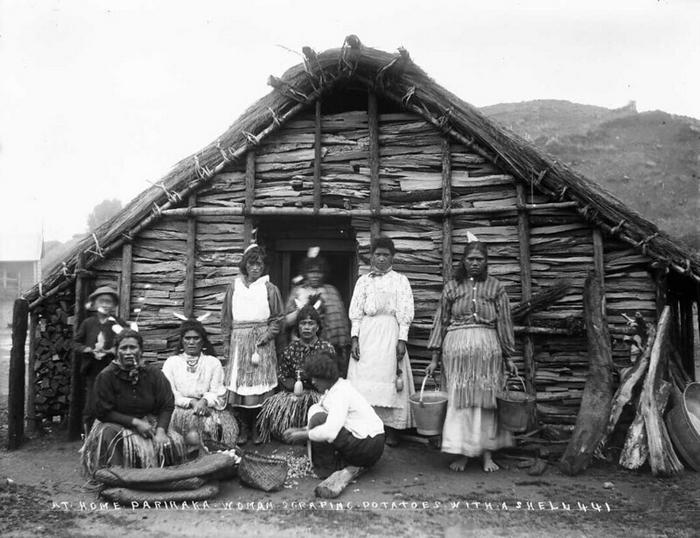

Modern cooking and heating appliances have reshaped marae kitchens and whare kai (kitchen and dining hall). Open fireplaces, known as kāuta, were the traditional places for Māori to prepare and cook kai. They also served as a place to gather, share news, tell stories and relive memories. Today, kāuta have largely disappeared from marae, due in part to the need to meet modern environmental, building and fire regulations. As memories fade of kāuta being used, so does the mātauranga Māori knowledge, tikanga traditions and reo or language, associated with their use.

Tau Iho I Te Po Trust, working with kaitiaki in Northland and Kaipara have partnered with Scion’s rural fire research team to address this loss of Māori heritage and culture. Together, they plan to bridge the gap between regulatory and cultural needs, by creating a set of engineering design requirements for modern kāuta.

Why reinstate kāuta?

Traditional kāuta were once central to marae culture and were the heart of important Māori hospitality and hosting traditions. The kāuta was a place for intergenerational learning, for passing down of mātauranga Maori, relationship building, and forming and remembering whenua and whānau history and tikanga.

Reinstating kāuta will enable the retention of traditional practices and knowledge while there is still a generation that has grown up with functional kāuta.

New regulations

New Zealand’s national and regional standards for buildings, air quality and fire safety will need to be factored in to any new designs. As of 2020, there are no specific regulations for kāuta, and researchers have had to base design requirements on the existing regulations for solid fuel burners (including cooking stoves). These requirements will also account for fire risk and will meet emergency services’ needs for fire risk reduction.

Evolving uses and value

To understand the cultural needs for a contemporary kauta (for example, for how many people a kāuta needs to cater for, construction, running and maintenance costs, location on the marae, how it can enable people to gather around it), the project team is engaging with Māori communities who experienced traditional kāuta.

Initial interviews revealed that as modern appliances have been adopted in marae, and kāuta have been decommissioned, there are few people with experience using traditional kāuta. Associated traditions, practices and language, distinct to regions, whānau and hapū have also declined.

Respondents also conveyed the changing uses for kāuta, explaining that while most were decommissioned because of environmental and fire regulations, change also came from evolving views about convenience and a shift in the way marae and whare kai are used by whānau (fewer people working in the whare kai means that electric and gas appliances are more convenient). These findings will help the project team understand what is needed to develop a contemporary kāuta design. To ensure the research team’s conclusions are appropriate, they will be reviewed by a Roopu Tikanga comprised of tangata Māori that work in fire management and kaumātua me kuia, that oversee the cultural integrity of the overall project.

Publicly available design standards

When complete, this project will have developed a set of engineering design requirements for a contemporary kāuta that meets cultural and regulatory expectations. These requirements will be made publicly available, allowing a resource to design contemporary kāuta prototypes.

Scion’s project leader, Ilze Pretorius states, “The relationships we are building with Tau Iho I Te Po enables co-design of a kāuta and helps us to place the design need in the cultural context”.

Waitangi Wood, from Tau Iho I Te Po Trust, has high hopes for the project. “Though times are changing, it’s this generation’s responsibility to ensure that the traditions and culture taught to us by our parents and grandparents are maintained and shared with current and future generations. The ability to manaaki our whānau and manuhiri, and our relationship with fire and other natural elements, are central to our culture and identity. We hope that the discussions informed by this project result in kauta being reinstated across Aotearoa, and that associated understandings, tikanga and language continues.”

The project is supported by Te Pūnaha Hihiko: Vision Mātauranga Capability Fund and is set to be complete in June 2021.