What will the new water standards mean for forestry?

Government’s freshwater reforms aim to balance economic growth with sustainability, and herald a change to the way freshwater is managed. Communities are now responsible for setting the standards for freshwater management within their region, creating the opportunity for forestry growers to be actively involved in the process.

Government’s freshwater reforms aim to balance economic growth with sustainability, and herald a change to the way freshwater is managed. Communities are now responsible for setting the standards for freshwater management within their region, creating the opportunity for forestry growers to be actively involved in the process.

Dr Brenda Baillie’s background in forestry and water quality saw her nominated to sit on the freshwater National Objectives Framework (NOF) reference group made up of representatives from iwi and public, private and academic sectors across the country, formed to advise and assist with the development of a National Objectives Framework. The framework is designed to guide regional councils in the setting of freshwater objectives and policies in their regional plans.

“It’s been an interesting process and often involved healthy discussion and debate within the group,” says Brenda. “Scientific information is critical, but just one of many factors that inform policy - there were also social, cultural, economic, business and political considerations.”

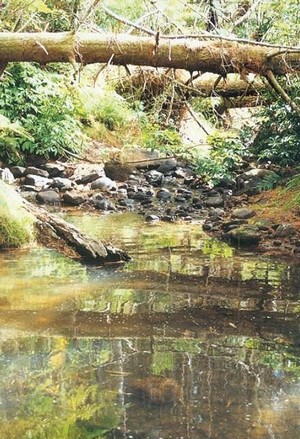

Lakes and rivers now need to meet minimum requirements for ecosystem health and human health for recreational purposes. Some of the attributes used to measure these two values, such as nitrate toxicity in rivers, have numeric standards assigned to them including national bottom lines, which are underpinned by robust science.

“More national numeric attributes will be included in the NOF over time but until then, it is up to regional councils to include attributes they consider appropriate to manage the freshwater values in their region,” explains Brenda. “Some councils have already started this process and are setting their own numeric limits for attributes such as sediment and nutrients, in consultation with their communities.

“This will be a big challenge for forestry - having enough people on the ground to be able to participate in these community processes and ensure forestry is not disadvantaged going into the future,” she says. “Another is the cyclic nature of forestry. Occasionally, forestry activities affect water quality – increased sedimentation as a result of harvesting for example. This needs to be balanced against the freshwater ecosystem services forestry provides for the intervening 20 or so years, but is something which is often overlooked.”

Chief Executive Warren Parker is encouraging forestry land holders to be actively involved in the consultation processes.

“Wider community consultation is already underway in the Bay of Plenty on rules for the allocation of nitrogen discharge limits on land holdings exceeding two hectares. Rural land holders have been informed and should get involved because the rules that are finally confirmed will define the scope of ‘sustainable’ enterprises for land units in the long term.”

The hard work of improving New Zealand’s fresh water is only starting and it is a process that will take decades. But the future of forestry and its contribution to water quality looks promising, with hearty discussions around sediment already taking place in some regions.

For further information:

Contact Dean Meason